Absolute Ko threat

J-zettaiko (ï¾Óß̤), no C, K-Àý´ëÆÐ(°¨)

A ko threat that cannot be ignored whatever happens.

An internal ko threat is an example because to ignore it makes the ko itself invalid.

A ko threat whose value is bigger then the ko is also an absolute ko threat.

Actual game

J-jissen (ãùîú), C-shizhan (ãùîú), K-½ÇÀü (ãùîú)

The moves that occur in a game, as opposed to variations that are not played.

Sometimes called the ¡®real game.¡¯ However, in writing an analysis of a game, it is redundant to use the phrase ¡®in the actual (or real) game.¡¯ Usually, it is better style to just write, ¡®in the game.¡¯

Aji (J)

See potential trouble.

Aji keshi (J)

See potential erasure.

Alive

J- iki (ß檡¢üÀª), C-huoqi (üÀѤ), K-»ì¾ÆÀÖ´Â

A state said of stones that cannot be killed by the opponent¡¯s attack.

It is also called ¡®settled,¡¯ ¡®living,¡¯ etc.

There are three ways in which stones can be alive.

1. when they have enough territory to survive an invasion

2. when they have two separate eyes or a high possibility of making them

3. when they are in dual life situation

Almighty Ko

J-tenka ko (ô¸ù»Ì¤), C-tianxia jie (ô¸ù»Ì¤), K-õÁö´ë(ô¸ò¢ÓÞ)ÆÐ

A ko so big that the player who wins it will win the game.

In such cases, it is useless to make a ko threat because the player who has taken the ko will not answer it.

Almost sente

J-jun sente (ñÞà»â¢) / han giki (Úâ즪), C-hou zhong xian (ý¨ñéà»), K-Áؼ±¼ö (ñÞà»â¢) / ¹Ý¼±¼ö (Úâà»â¢)

A play that doesn¡¯t absolutely force a local answer, but has a large follow-up which is very profitable.

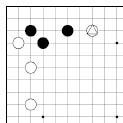

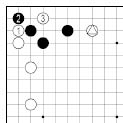

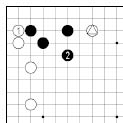

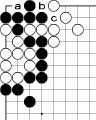

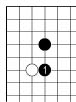

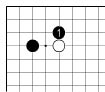

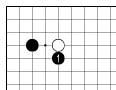

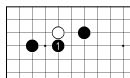

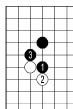

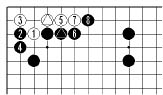

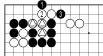

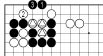

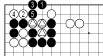

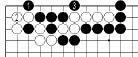

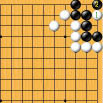

In Dia. 1, the marked white stone does not absolutely force Black to answer, but is almost sente. If Black ignores it and plays elsewhere, White will attack the black stones with 1 and 3 in Dia. 2. So, Black cannot bend at 2 in Dia. 2 and has to jump out with 2 as in Dia. 3. This result is profitable for White, since he gains many points in the corner by playing 1 in sente.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2  Dia. 3

Dia. 3

Angle move

J-kado (ÊÇ), no C, no K

A move played at a point diagonally above or below an opposing stone.

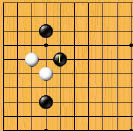

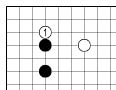

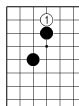

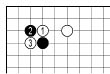

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2

Black 1 in Dia. 1 and White 1 in Dia. 2 are examples of ¡®angle moves.¡¯ Since the Japanese ¡®kado¡¯ is a general term which includes special cases and so is ¡®angle move¡¯, it is not very relevant to give only one example. Actually there are other examples of ¡®angle move¡¯ such as ¡®shoulder-hit¡¯ and ¡®Jaw attack.¡¯ In the Korean and the Chinese terminology, there is no word covering all these cases, but there are words indicating each case.

Approach

J-kakaru (ÎЪë), C-guajiao (?ÊÇ), K-°ÉÄ¡´Ù

To come close to an opponent¡¯s stone occupying a corner. There should be at least one-space distance between the stone in a corner and the approaching stone.

All the three Asian terms have the same literal meaning as ¡®hang on,¡¯ since the approaching move looks like hanging something on a peg (a stone in the corner.) The word ¡®approach¡¯ is also used for extensions that come close to an opposing stone or position regardless of its location, as in the proverb, ¡®Don¡¯t approach thickness.¡¯ The usually usuage for ¡®approach¡¯ is for attacking a stone in a corner. However, there are others that are distinguished by different terms.

Cf. come close to

Low vs. high approach

When an approach move is on the third line, it is a ¡®low¡¯ approach, and when it is on the fourth, a ¡®high.¡¯

low vs. high

low vs. high

low vs. high

low vs. high

One-space approach

J-ikken kakari (ìéÊàÎЪ«ªê), C-yijian gua (ìé??), K-ÇÑ Ä °Éħ

An approach move that is a one-space jump from the opponent¡¯s stone in a corner, such as White 1 in Dia. 1.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Two-space approach

J-niken kakari (ì£ÊàÎЪ«ªê), C-erjian gua (ì£??), K-µÎ Ä °Éħ

An approach move that is a two-space jump from the opponent¡¯s stone in a corner, such as White 1 in Dia. 1.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Double approach

J-ryogakari (å»Ìýªê), C-shuangfeiyan (??æØ), K-¾ç°Éħ

A second approach move against a corner, such as White 1 in Dia. 1.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Knight¡¯s approach

J-keima kakari (ª±ª¤ªÞª«ª«ªê, ÌýØ©ÎЪ«ªê), C-xiaofei gua (á³??), K-³¯ÀÏÀÚ °Éħ

An approach move that is a knight¡¯s move from the opponent¡¯s stone in a corner, such as White 1 in Dia. 1.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Large knight¡¯s approach

J-ogeima kakari, (ÓÞÌýØ©ÎЪ«ªê)¡¢C-dafei gua (ÓÞ??), K-´«¸ñÀÚ °Éħ

An approach move that is a large knight¡¯s move from the opponent¡¯s stone in a corner, such as White 1 in Dia. 1.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Approach-move ko

J-yose ko (Ðöª»Ì¤), C-songqi jie (áæ?̤) / huanqi jie (??̤), K-´Ã¾îÁø ÆÐ

A ko in which a player needs to spend one or more moves, filling one or more outside liberties of the opponent¡¯s stones before he can start the ko.

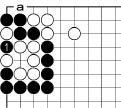

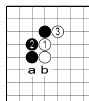

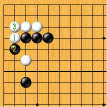

The ko started by Black 1 in Dia. 1 is an example of an one-move approach ko for White. He cannot connect at 1 to win the ko, so he must use a move to fill Black¡¯s outside liberty at ¡®a.¡¯ Once White has played at A, it becomes a real ko because White can end the ko by capturing the four black stones.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2

In Dia. 2, White has to spend three moves in filling Black¡¯s liberties at ¡®a,¡¯ ¡®b,¡¯ and ¡®c¡¯ in order to make the ko on the left side a real ko. It is called a three-move approach ko.

The Chinese song qi (áæ?), huan qi (??), and the Korean ¡®´Ã¾îÁø¡¯ literally mean ¡®loose.¡¯

Atari (J)

J-atari (?ª¿ªê), C-dachi (öèýÞ), K-´Ü¼ö (Ó¤â¢)

An immediate threat to capture, which leaves the opponent¡¯s stone(s) with only a single liberty.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

White 1 in Dia. 1 puts the black stone in atari. Now Black has only one liberty at ¡®a¡¯, so he should put a stone there in order not to be captured.

The Chinese and the Japanese names both literally mean ¡®hit¡¯ or ¡®strike,¡¯ and the possible English translations must have a wide meaning. It is problematic when a term does not have a clear meaning. On the contrary, the Korean name for ¡®atari (dansoo)¡¯, literally meaning ¡®one liberty,¡¯ explains the situation precisely. I have suggested calling it ¡®dansoo¡¯ in Jungsuk in Our Time (2001).

In English usage, ¡®atari¡¯ is used as an English word, so when one use it as a verb it is permissible to use the ending ¡®es.¡¯ If one use it as a plural, then you could say: ¡®The two ataris of Black 1 and 3 . . .¡¯

Counter-atari

J-ate kaeshi (?ªÆÚ÷ª·), C-fan da (Úãöè), K-µÇ´Ü¼ö

An atari played against the opponent¡¯s stone that has put a friendly stone(s) in atari.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

In Dia. 1, White 1 ataries the marked black stone. Black 2 is a counter-atari against White 1.

Double-atari

J-ryoatari (å»Óת¿ªê), C-shuangchi (?ýÞ)£¬K-¾ç´Ü¼ö (å»Ó¤â¢)

A play that gives atari to two individual stones or two separate groups simultaneously.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

White 1 in Dia. 1 ataries the two sets of Black¡¯s marked stones.

Attach

J-tsukeru (Üõª±ªë), C-tuo (öõ) / kao (?) / peng (?) / ding (?), K-ºÙÀÌ´Ù

A play touching the opposing stone when there is no friendly stone on the next line.

In English there is a word which looks very similar to ¡®attachment¡¯, namely ¡®contact play.¡¯ It refers to many kinds of moves that are made directly next to the already-played enemy stone. However, I don¡¯t think it is right to use the word ¡®contact play¡¯ because it can also include ¡®cut¡¯ or ¡®atari¡¯ and those have nothing to do with ¡®attaching.¡¯ In fact, there are moves that touch and contact the other stones but have different meanings and different purposes, so it is impossible to include them in one concept like ¡®contact play.¡¯ They are not derived from a single concept, but actually are independent of each other. Even, the Chinese terminology has no general word that includes all kinds of attachments. Instead they classify them by different names according to their purposes and shapes.

Diagonal attachment

J-kosumi tsuke («³«¹«ß«Ä«±), C-jianding (ôÓ?), K-ÀÔ±¸ÀÚ ºÙÀÓ

A diagonal play made in contact with an enemy stone. Black 1 in Dia. 1 is an example.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Side attachment

J-yoko tsuke (?Üõª±), C-peng (?), K-¿·ºÙÀÓ

An attachment on the same line as the opposing stone.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Underneath attachment

J- shita tsuke (ù»«Ä«±), C-tuo (öõ), K-¹ØºÙÀÓ

An attachment one line lower than the enemy stone.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2

Upper attachment

J- ue tsuke (ß¾Üõª±), C-kao (?), K-À§ºÙÀÓ

An attachment one line higher than the enemy stone.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2

Attach across the knight¡¯s move

J-tsuke kosu (Üõª±êƪ¹), C-kua (Î¥), K-°Ç³Ê ºÙÀÌ´Ù

To play an attachment or a knight¡¯s move across a knight¡¯s move of the enemy.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2

Attach and block

J-tsuke osaeru (Üõª±ä㪵ª¨ªë), no C, K-ºÙ¿© ¸·´Ù

To attach and then to block.

In Chinese terminology, it is hard to find an idiom that binds the two words ¡®attach¡¯ and ¡®block.¡¯

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Black 1 is an attachment and 3 is a block.

Attach and cut

J-tsuke giru (Üõª±ï·ªë), C-kao duan (??) / tuo duan (öõÓ¨), K-ºÙ¿© ²÷´Ù

To attach and then to crosscut after the opponent bends.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

White 1 is an attachment and 3 is a cut.

Attach and pull back

J-tsuke hiku (Üõª±ìÚª¯), C- tuo tui (öõ÷Ü), K-ºÙ¿© ²ø´Ù

To attach and then pull back.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

White 1 is an attachment and 3 is a pulling back.

Attach and stretch

J-tsuke nobu (Üõª±ãߪÖ) / tsuke sagaru (Üõª±ù»ª¬ªë), C-ya chang (?íþ)£¬K-ºÙ¿© ´Ã´Ù (»¸´Ù)

To attach and then stretch.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Attack

J-semeru (Íôªáªë), C-gong ji (Íô̪), K-°ø°Ý(Íô̪)ÇÏ´Ù

A generic term for all the plays that reduce the opponent¡¯s territory, prevent a framework from becoming a territory, threaten the opponent¡¯s group in order to make strength, territory, or influence while chasing them, or kill the opponent¡¯s stones.

Avalanche

J-nadare (àäÝÚ), C-xuebeng (àäÝÚ), K-¹Ð¾îºÙÀ̱â / ´«»çÅÂ

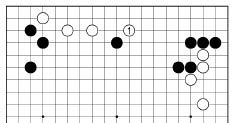

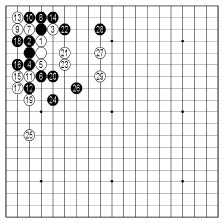

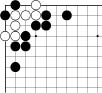

The name of a joseki shown in Dia. 1.

The white stones at 1 and 3 press down on the black stones much like an avalanche, burying the black stones against the side, while the white stones stay on top.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

This pattern begins with White¡¯s push at 1 in Dia. 1. If Black next plays at ¡®a,¡¯ it becomes the ¡®large avalanche joseki¡¯ and Black ¡®b¡¯ leads to the ¡®small avalanche.¡¯ The sequence shown in Dia. 2 is an example of a ¡®large avalanche.¡¯ The resulting position covers almost a quarter of the board.

Dia. 2

Dia. 2

The sequence shown in Dia. is an example of the variations made by Black ¡®b¡¯ in Dia. 1. It is called the ¡®small avalanche.¡¯

Dia. 3

Dia. 3

Awaken

No J, no C, K-¿òÁ÷ÀÌ´Ù

To add moves in order to utilize a possibility having been left for later use.

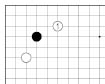

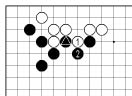

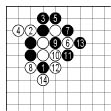

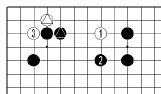

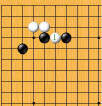

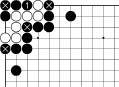

In Dia. 1, White exchanged ¡â and ¡ã time ago to see if he could use ¡â later. It would be dangerous for him to bend at 1 in Dia. 2 and try to live in the corner in this position, but if, for example, White 1 and Black 2 are played as in Dia. 3, then it¡¯s plausible that White could live in Black¡¯s area. In this case, White ¡â is a ¡®sleeper¡¯ and White 3 ¡®awakens¡¯ the sleeper.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Dia. 2

Dia. 2  Dia. 3

Dia. 3

Bad shape

J-gukei (é×û¡), C- yuxing (é×û¡), K-¿ìÇü (é×û¡)

A shape that fails to work well because it is inefficient or has weaknesses.

¡®Bad shape¡¯ in English can mean a shape has too many cutting points, but in Asian languages, the character ¡®éס¯ literally means ¡®dumb¡¯ and so refers usually to inefficient shapes such as the ¡®empty triangle¡¯ or the ¡®dumpling shape.¡¯ A shape that has many weak points can be just ¡®dangerous¡¯ or ¡®bad¡¯ but not ¡®dumb.¡¯ However, I think it is fine to have a term including all kinds of ¡®bad¡¯ shapes since there are already individual names for especially ¡®dumb¡¯ shapes in Go.

Baduk

Korean name for go.

The Korean terminology has a unique Korean name ¡®Baduk¡¯ which has nothing to do with the Chinese Character ¡®êÌѤ.¡¯ The name ¡®Baduk¡¯ is even found in a document from the 17th century Chosun (ðÈàØ) Period, and is believed to have been used long before the 17th century.

Balanced

J-gokaku (û»ÊÇ), C-liangfen (å»ÝÂ), K-È£°¢ (û»ÊÇ)

The result of a sequence that is fair and satisfactory for both players.

Usually used to evaluate the result of a pattern. For example, the result is well balanced between territory and influence.

Bamboo joint

J-Takefu (ñÓï½), C-shuang (äª), K-½Ö¸³ (äªØ¡)

A very strong and effective way of connecting, which looks like bamboo joint.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

It refers to the shape made by the four black stones after Black 1 in Dia. 1. It is a very strong connection, and White can¡¯t cut it as long as Black answers properly.

Dia. 2

Dia. 2

Actually, connecting with Black 1 in Dia. 2 is much stronger connection, but Black 1in Dia. 1 gives the black stones better shape: it has an effect on the three white stones on the left and it projects influence towards the center. A bamboo joint is a strong connection as well as an efficient shape.

The Japanese term ¡®takefu¡¯ is taken from the shape that resembles bamboo joint itself. On the other hand, the Chinese and Korean ¡®shuang (äª)¡¯ and ¡®½Ö¸³ (äªØ¡)¡¯ mean two pairs of stones that stand in line with each other.

Bang-naegi

K-¹æ³»±â

A Korean gambling method to bet money according to the actual count of a game.

¡®Bang¡¯ is a unit that is used for counting 10 points as a bundle. ¡®Naegi¡¯ literally means a ¡®gambling¡¯ or ¡®betting.¡¯

In a Bang-naegi, a certain amount of money is bet for each Bang, for example, one dollar for each Bang. A Bang is decided in this way: 1~10 points difference means one Bang, 11~20 means two Bang, 21~30 means three Bang, and so on. It continues until nine Bang, called ¡®Mahnbang.¡¯ ¡®Mahn (Ø¿)¡¯ literally ten thousands, but is often used as a prefix meaning ¡®an enormous amout.¡¯ Because Mahnbang is the maximum, it doesn¡¯t make any difference to win by 81 points or more, and a resignation is also considered the same as ¡®Mahnbang.¡¯

The most interesting thing about of Bang-naegi is that both players have to do their best until the game is finally counted, so it is not easy to resign. In a normal game, the winner doesn¡¯t want to take risks, and the losing player resigns when he sees he has not chance of winning, as we see in professional games. But, in Bang-naegi, it is not reasonable to resign before one is certain of losing by more than 90 points, and to stop fighting for more points if he is winning by five points. Therefore, even after the game is decided, it is meaningful for the players to want to fight on.

Base

J-ne (ÐÆ), C-gen (ÐÆ), K-±Ù°Å (ÐÆËà)

An occupied area in a corner or on a side that is large or thick enough to guarantee that the stones which surround it can make two eyes if they are attacked.

The Korean ¡®±Ù°Å¡¯ literally means ¡®a place to take root.¡¯ If ¡®a group of stones has no base¡¯, the group has no ¡®root¡¯ in a corner or on a side, so that, if it is attacked, it has to escape into the center as the white stones do in Dia.1

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Belly attachment

J-haratsuke (ÜÙÜõª±), no C, K-¹èºÙÀÓ

An attachment played at the side of two enemy stones in order to reduce their liberties and to win a capturing race by using the fact that the opponent¡¯s stones are positioned in the corner.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2

White 1 in Dia. 1 is a belly attachment and he can win the capturing race as shown in Dia. 2. If White just bends at 1 as in Dia. 3, he will lose the capturing race because he has one less liberty.

Dia. 3

Dia. 3

In Chinese, there is no word which distinguishes this move from a general clamp.

Belly-Drum

J-tanuki no haratsuzumi (×áªÎÜÙÍÕ), C-huangyin pu die (???ïÊ), no K

A very unusual knack of killing the opponent¡¯s stones which don¡¯t seem to be in danger.

Black 1 in Dia. 1 is a good move that kills the three marked stones, and Black 3 in Dia. 3 is another clever move to frustrate White¡¯s effort to escape.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2

Dia. 3

Dia. 3  Dia. 4

Dia. 4

The Japanese term literally means ¡®raccoon-dog¡¯s belly-drum¡¯ and the Chinese ¡®a bird takes (eats) a butterfly.¡¯ There is no equivalent in Korean.

Bend

J-hane (Ô¯ªÍ), C-ban (?), K-Á¥È÷´Ù

A move played diagonally from a friendly stone to block the opponent¡¯s stretching when stones of both sides are standing abreast.

Black 1 in Dia. 1 is an example of a bend.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

So far, the Japanese ¡®hane¡¯ has been used. For example, the Dia. is explained as ¡®Black plays hane with 1.¡¯ The Japanese ¡®hane¡¯ means literally ¡®splash.¡¯

¡®Bend¡¯ is an English word well translated from the Chinese ¡®ban(?)¡¯ and the Korean ¡®Á¥È÷´Ù.¡¯ Those words are describing the action of bending a joint in a game like hand wrestling, which is because the play like Black 1 Dia. figuratively reminds of that action.

One thing that should be kept is to distinguish ¡®bend¡¯ from ¡®turn.¡¯ In ordinary English usage, those two words share the same meaning, but in Go, each word refers to two completely different moves. So to speak, ¡®bend¡¯ is a move played at a 45-degree angle from a friendly stone while ¡®turn¡¯ is a move played at a 90-degree (right) angle from a friendly stone.

Cf. turn.

Bend inside vs. Bend outside

Inside vs. outside

Inside vs. outside

An inside bend goes for profit, whereas an outside bend strives for influence.

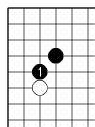

Counter-bend

J-hane kaeshi (ªÏªÍÚ÷ª·), C-fan ban (Úã?), K-µÇÁ¥Èû

To bend as an answer to an opponent¡¯s bend when a stretch is usually expected.

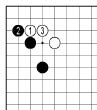

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2

In Dia. 1, Black 2 is a counter-bend. Usually Black 2 in Dia. 2 is expected.

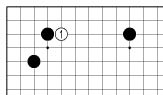

Double-bend

No J, C-liangban (å»?), K-¾ç Á¥Èû

A technique to increase the number of liberties by bending twice to the left and to the right in capturing race.

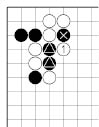

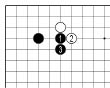

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2

In Dia. 1, the black stones have three liberties and the white stones have four liberties, so Black is one liberty behind. But, if Black can play 1 in Dia. 2 in sente and bend with 3, then the number of liberties of the black stones increases, so Black can win the capturing race.

Bend and connect

J-hane tsugu (Ô¯ªÍÜõª°), C-ban jie (?ïÈ)£¬K-Á¥Çô ÀÕ´Ù

To bend and then connect.

It differs from the usage of ¡®bend and wedge,¡¯ which refers to ¡®a move¡¯ not ¡®a series of moves.¡¯

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

White 1 is a bend and 3 is a connection.

Bend and cut

J-hane kiri (Ô¯ªÍï·ªê), C-ban duan (??), K-Á¥Çô ²÷´Ù

To bend and then cut when the opponent also bends.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

White 1 is a bend and 3 is a cut.

Bend and kill

J-hane-gorosu (Ô¯ªÍ-߯ª¹), C- bandian si (?ïÃÞÝ), K-Á¥Çô Àâ´Ù

Killing stones by bending to reduce the opponent¡¯s eye-space and then hitting their vital point.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

The combination of White 1 and 3 in Dia. 1 is an example.

Bend-and-wedge

J- hane komu (Ô¯ªÍ-?ªà), no C, K-Á¥Çô ³¢¿ì´Ù

To bend as well as to wedge in between two opposing stones as White 1 in Dia. 1.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

There is no word in Chinese which distinguishes it from just ¡®wedge (wa(?)).¡¯

It is also called ¡®wedge in.¡¯

Bent four

J-magari shimoku (Íت¬ªêÞÌÙÍ) / kyokushi (ÍØÞÌ), C-wansi (?ÞÌ), K-°î»ç±Ã (ÍØÞÌÏà)

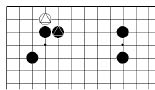

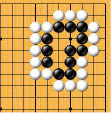

The four-point eye space that is shown in Dia. 1.

It is perfectly alive, except when it happens in a corner as shown below.

Bent four in the corner

J-sumi no magai shimoku (éêªÎÍت¬ªêÞÌÙÍ), C-panjiao qusi (?ÊÇÍØÞÌ), K-±Í°î»ç

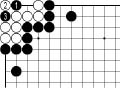

Different from a normal ¡®bent-four,¡¯ the ¡®bent-four in the corner¡¯ shape is not perfectly alive.

In Dia. 1, if Black adds a move, then it is alive, but, if White plays 1, it will become a ko.

Bent four in the corner considered dead by the rules used in Korea and Japan

The White¡¯s eye space in Dia. 1 is not exactly ¡®bent four¡¯ but, in Korea and Japan, it is considered as ¡®dead¡¯ because it can become a ¡®bent four.¡¯

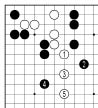

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

It is obvious that White can¡¯t play 1 in Dia. 1 because his stones will be killed by Black 2. On the other hand, Black has to fill all the marked point in Dia. 2 and play 1 in order to make White¡¯s eye space a bent four in the corner. However, Black still can¡¯t kill White¡¯s stones without fighting a ko with 1 and 3 in Dia. 3. That is what happens if there is no rule about this position.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Dia. 2

Dia. 2  Dia. 3

Dia. 3

Of course, it is possible for Black to begin the ko fight after erasing all the possible ko threats by adding moves before starting the ko. But, unlike the Chinese counting rule where a player doesn¡¯t lose points by playing inside his territory, under Korean and Japanese rules it can be a big loss to play inside of one¡¯s own territory in order to remove the opponent¡¯s ko threats.

Therefore, it is necessary in Korean and Japanese Go to make a special rule to decide this situation in order to get the same result as the Chinese rules. In the Chinese rules, it is clear that the white stones in the corner will die and it doesn¡¯t need to be confirmed by actually playing it outs. This is the reason that the Korean and the Japanese have the rule ¡®When only one player can make a ko, and the other player can do nothing but kill himself, the group of the latter is considered to be dead without further play.¡¯

Big eye vs. small eye

J-onakakonaka (ÓÞñéá³ñé), C-dayan sha xiaoyan (ÓÞäÑ?á³äÑ), K-´ë±Ã¼Ò±Ã (ÓÞÏàá³Ïà)

This is a proverb that says in a capturing race between two one-eyed groups with eye space of different size, the group with bigger eye space wins the race.

When there is a capturing race between two groups, one with 2-point eye space and the other with 3-point eye space, it is easy to know who is going to win the race because the number of liberties in the eye space is the same with the number of empty points in them. However when the size of eye space is bigger than four-point eye space, the number of liberties in it becomes more than the number of points in it.

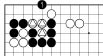

For example, as shown below, White has to spend eight moves to capture the Black stones that originally had a five-point eye space. The marked white stones are not counted because Black also has to spend a move for each. So in a five-point eye space, there are eight liberties.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2  Dia. 3

Dia. 3

In this way, a four-point eye space has five liberties, a five-point eye space has eight, a six-point eye space has twelve, etc. The proverb ¡®big eye vs. small eye¡¯ says that the side that has the larger eye space will win the capturing race.

The translation of ¡®big eye vs. small eye¡¯ comes from the Chinese term. In Korea, ¡®palace(±Ã(Ïà))¡¯ is used instead of ¡®eye¡¯ and in Japan, ¡®inside(naka(ñé)).¡¯

Bilateral gote endgame

See gote.

Bilateral sente endgame

See sente.

Black-and-Even game

J-senaisen (à»ßÓà»), C-xianxiangxian (à»ßÓà»), K-¼±»ó¼± (à»ßÓà»)

One of the handicap rules which gives the weaker player the chance to take Black in two games out of three, i.e. to play the first game in Black and to play the second and the third in even game rule.

It came from the Japanese professional handicap rule for a 1-dan difference in the Edo period.

Block

J-osaeru (ä㪵ª¨ªë), C-dang (?)£¬K-¸·´Ù

To stop the opponent¡¯s advance with a contact play.

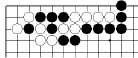

There are many kinds of blocking moves like Black 1 in the next four diagrams.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1  Dia. 2

Dia. 2

Dia. 3

Dia. 3  Dia. 4

Dia. 4

Blockade

J-fusa (Üæáð), C-feng (Üæ), K-ºÀ¼â (Üæáð)

To confine the opponent¡¯s stones by blocking the outside so that the opponent can¡¯t come out.

The white stones in Dia. 1 have to live within Black¡¯s blockade because it can¡¯t expect to break out into the center.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Break an eye

See eye.

Breaker for two ladders

See ladder breaker.

Break out

J-saitederu (ùܪ¤ªÆõóªë), C-chongchu (õúõó), K-¶Õ°í ³ª°¡´Ù

To escape from the opponent¡¯s blockade to an open space.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

White succeeds in breaking out the blockade with the sacrifice of White 1.

Break through

J-sabaki (ø¤ª), shinogi (×Ъ®), C-tengnuo (??), K-Ÿ°³ÇÏ´Ù (öèËÒ)

To get out of danger without suffering unacceptable damage in the process.

The Japanese ¡®sabaki¡¯ literally means ¡®handling skillfully¡¯ and the Korean ¡®Å¸°³¡¯ means ¡®breaking through a certain situation,¡¯ and both word are used when one saves his isolated group of stones having difficulty in settlement in the middle of the enemy¡¯s influence with light moves. The Japanese ¡®shinogi¡¯ literally means ¡®to survive or to withstand¡¯ a distressing situation also means ¡®to rescue endangered stones.¡¯

Bridge

See go over

Bulge

J-fukurami (ø³ªéªß), C-gu (ÍÕ), K-ºÎÇ®´Ù

A play that makes the shape of tiger¡¯s mouth to strengthen a one-space jump.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Black 2 in Dia. 1 is an example.

It is also called ¡®swell out.¡¯

Bump

See butt

Butt

J-tsukiataru (Ôͪ?ªë), C-ding (ð¢), K-Ä¡¹Þ´Ù

A contact play colliding against the already placed opponent¡¯s stone.

Black 2 in Dia. 1 is an example.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1

Butterfly formation

J- kannon biraki (?ëåªÓªéª), no C, no K

A formation that is made up of two large knight¡¯s moves from a stone on a corner star point.

It has a potential problem at the 3-3 point, where the opponent can invade and form a living group in the corner.

Dia. 1

Dia. 1